Posted 17 Feb 2010

The net neutrality debate is festering like a tropical storm still out at sea although no-one seems to define net neutrality with FCC net neutrality legislation.

Technological advancements have served to hasten distribution or both physical and intellectual goods which have provided the foundation for humanity to build their economies upon. From 'roads of rails' in 1550 to the invention of the pressure cooker in 1679 to the driving of the golden spike at Promontory Summit in 1869 there has been a relentless advance of technology to connect the world and it has shaped it economically, politically and legally.![]()

![]()

From contract to tort to property law the railroads left an indelible stamp on American jurisprudence as they advanced and because of the tremendous natural endowment of the land of plenty, America, has presided over the most materially prosperous era of history.

And the impact the railroads have had on humanity pale in comparison to the effect of the four decade old Internet. As H.R. 3458 Internet Preservation Act of 2009 and others show, the rules are still being written.

The Internet has already resulted in the most advanced monetary evolution the world has ever seen. From credit cards and cell phones to stock exchanges and ecommerce; from New York to Karachi and Frankfurt to Shanghai everyone has been impacted. And the surface has only been scratched with the most exciting advancements still in the future to be adopted like Apple's iPad, digital gold currency, and other science fiction dreams of ancient year.

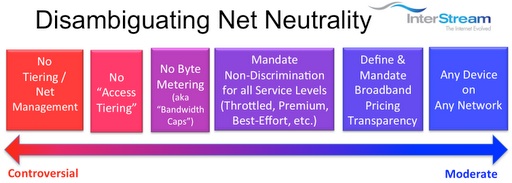

The net neutrality pros and cons which shape the debate are more complex than simple soundbites. In January 2009 I attended a presentation about disambiguating net neutrality. To provide a solid overview for you I invited the presenter to prepare a guest post (Any persuasive views are his own and do not represent RunToGold's position).

Over the past several months, I have spent time in Washington D.C. attempting to better understand the participants and issues at the center of the net neutrality debate. As in many Washington debates, while both sides are passionate about their positions, the challenge is to separate rhetoric from core concerns and identify specific areas where common ground exists as the basis to establish a consensus driven solution.

Since reasons to be against net neutrality are not limited to within domestic boundaries, solutions designed to address net neutrality should work anywhere in the world.

This article seeks to engage commercial interests and public interest groups worldwide in meaningful discussion and work toward achievable consensus on “net neutrality” and "reasonable network management" practices. Achieving consensus definitions to these key terms is the first step in the process of arriving at workable solutions amongst all parties - domestic and international.

Internet neutrality attracts a wide spectrum of positions, from the more extreme and controversial, to the moderate that advocate reasonable practices through industry self-restraint or group consensus, which could be a starting point for consensus amongst Internet Service Provider (ISP) and public interest participants. Therefore, to define net neutrality or at least that portion being discussed is essential for there to be meaningful dialog in the net neutrality debate.

To help define net neutrality, the right side of the diagram above, depicts the broad agreement that exists to reaffirm a consumer or business’ right to connect an IP-based (i.e. IP as in Internet TCP/IP protocol) device to a wired or wireless network. In addressing the right to connect an IP device to the network, I take no position on concerns raised regarding any specific relationship and/or offering between a carrier and device manufacturer for example, between AT&T (T) and Apple (AAPL) – and whether such relationship or offering constitutes a violation of device exclusivity net neutrality principles.

This discussion’s focus is solely on IP-based connectivity and does not address ancillary wireless services that involve specific wireless carriers, hardware makers, or other value-added services above that Internet Protocol (IP) layer (this is not to say that wireless IP-based connectivity cannot or should not fall under the model). Communication services that offer IP-based connectivity should clearly allow for any IP-based device to access the Internet via a wired or wireless connection.

Therefore, a sustainable broadband solution need not address value-added relationships (e.g., the iPhone or new iPad) or specific carrier partnerships. Instead, our main focus is on preserving IP connectivity for end-to-end services across the network. When the diagram says any device on the network, we infer that any IP-connected device can access other IP-level services on the other side of the network.

Continuing to define net neutrality, reading to the left, pricing transparency refers to giving consumers greater information and clarity regarding their service beyond providing more definition of “up to” speeds. For example, advertisements promise 10 Megabit per Second (Mbps) broadband services for consumers’ homes or offices.

Yet, descriptions of the actual speeds contained in terms of service typically reveal why, in most cases, these connections represent “up to” speeds.

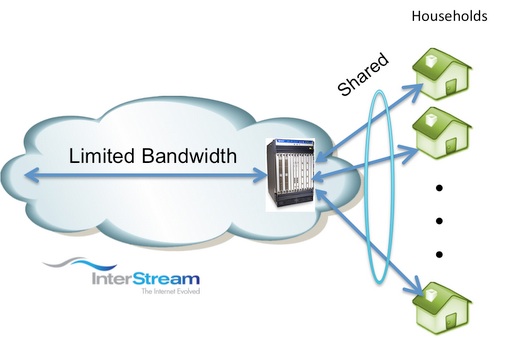

These “up to” speeds result from many homes and businesses that share an upstream connection to the Internet's backbone networks, while also sharing downstream 10 Mbps connections all through a much smaller link with limited bandwidth. Under these network realities, American households and small businesses cannot possibly receive 10 Mbps everywhere, all the time, irrespective of what “up to” speed the broadband ISP represents in its marketing.

Therefore, the typical consumer or small business rarely receives the “advertised” 10 Mbps connection directly to the Internet, since the connection is shared amongst many in a neighborhood or region. This network configuration is actually similar to the old phone system, where many households and businesses shared common network equipment that supported the basic telephone.

While many consumers typically shared these phone connections, a high degree of reliability existed in getting a dial tone and making a call whenever you picked up the phone. This superior reliability is due in large part to the engineers who designed and operated the network based on the fact that every person would not make calls at the same time. To design the properly sized network, however, they used complex statistical models to predict peak call loads and call duration on how telephony connections were statistically shared.

The difference between the phone system and the Internet lies in the fact that an "Erlang model or formula" existed for the phone system. The Internet, however, lacks a similar formula because no stable and reliable statistics exist by which ISPs can easily ascertain how much capacity they must offer in order to guarantee objective measures for service quality and provide a customer experience that meets or exceeds expectations.

In the telephone network, it is commonly known that “Mothers Day” is the typical peak load period for use by residential consumers. During this day, calling volumes above the statistical norm would often result in higher rates of a lack of dial tone or blocked calls. Similarly, broadband networks can also be overwhelmed both on a daily and during certain peak usage hours. Without an Erlang formula for broadband, there is no way to quantitatively measure the broadband consumer’s quality of experience for the variety of applications they consume.

Achieving service transparency in the broadband world will require some form of statistical certainty. Any advertised residential or commercial Internet service offering should have a statistical probability. Formulating greater statistical certainty becomes more challenging as broadband networks become more tiered and manage.

For example, there are certain applications, such as peer-to-peer (P2P), which may be throttled back during periods of congestion so that other users do not receive a degraded experience. Given these challenges, both consumers and the industry require specific proposals for offering quantifiable metrics for transparency under tiered (or network managed) service offerings.

We should encourage industry and public interest groups to support integrating simple best-effort transparency metrics with a more sophisticated tiered approach.

Industry and public interest groups have recently been making good progress in this area and are attempting to reach consensus on how best to inform and represent the broadband consumer data and information on what they are purchasing in terms of performance, reliability, and application compatibility.

In addressing these issues, the topic of non-discrimination creates greater challenges-- particularly in the context of the FCC net neutrality legislation such as FCC's NPRM's paragraph 106. Traditionally, non-discrimination refers to offering a customer the same rate, terms and conditions that was previously offered to a similar (e.g. residential or commercial) customer. During the net neutrality debate, certain proponents advocating FCC net neutrality legislation and regulation appear to conflate non-discrimination with a ban on access tiering.

How do these two issues with FCC net neutrality legislation overlap in the net neutrality debate when parties presume that the broadband networks and Internet in general will, going forward, remain "flat" under a best-effort service model? If broadband networks remain "flat" and no form of tiered (or network managed) services exist, then some would consider it discrimination if an application service provider (e.g. website operator) were to pay for enhanced or prioritized service to “speed up” one website over another.

Some FCC net neutrality legislation advocates have encapsulated this notion in a sound bite that it would be "unfair for some web sites to receive preferential treatment to reach consumers over others due to special behind-the-scenes business deals struck with their broadband providers." However, the sound bite is inaccurate because site operators do not typically buy service directly from a broadband ISP.

In fact, they host their content at some data center, which, in turn, purchases bandwidth from another ISP that ultimately reaches the consumer's broadband network. Only firms with significant IP traffic, like Google (GOOG) or Microsoft (MSFT) have direct service agreements with broadband networks.

On the other hand, small website operators that seek to distribute video from their sites typically buy content delivery network (CDN) services from providers such as Amazon (AMZN), Akamai (AKAM) or Limelight (LLNW). Those CDNs save costs in terms of bandwidth in addition to offering better performance due to the anomaly (or some might say "bug") in the way the TCP protocol works over shorter latencies on the net today.

The average peer-to-peer downloads, whether the Superbowl, feature-length movies or Linux distribution consumes an enormous amount of bandwidth that can take hours if not days. During that period, a consumer initiating this type of peer-to-peer download would consume the existing limited bandwidth and would interfere with a neighbor's web surfing experience.

The core issue is not whether speeding up one website over another is discriminatory, but rather how to offer service levels appropriate for different types of applications.

All consumers are entitled to receive their desired quality of experience for each application they wish to use via broadband. Does it not make sense that consumers may demand differing quality of services depending on the application, like watching the Superbowl live as opposed to reading email?

Neutral third party standards are a mechanism that can be implemented as a foundation to establish “non-discriminatory” tiered, managed networks, with bedrock rational industry practices that advance non-discrimination across all tiers of service.

These practices must work hand-in-hand with the pricing and service level policies so that consumers and website owners alike are informed more transparently of their levels of service. By offering hard metrics for each application’s service level, and insuring that those metrics are reported via a neutral third party, the Internet’s current best-effort delivery model can bolster an objective means to prohibit discrimination.

Many advocates for “keeping the net neutral” argue against byte metering or bandwidth caps. Some contend that if cable or telephone companies, for instance, could set overly low or restrictive limits on the amount of data consumed, then these same companies could directly encourage their subscribers to stick with their ordinary broadcast television service instead of seeking other competitive "over the top" Internet video offerings.

As industry analyst Colin Dixon recently pointed out with regard to Netflix (NFLX), bandwidth caps would "kill the[ir] streaming business overnight." Caps, particularly small ones, as proposed by Time Warner cable last year, could represent a barrier or delay to pervasive Internet video adoption.

Countries like New Zealand and Australia already charge by the byte when it comes to Internet usage. The Internet consumption patterns in Australia and New Zealand of broadband applications is quite different from the rest of the world. Economics guide behavior and behavior guides culture. Since Internet video streams and files tend to be quite large the users tend not to consume as much.

Arguments against best-effort usage bandwidth caps or charges come fundamentally down to economics. Wired broadband and wireless networks both share the characteristic of having high fixed capital cost outlays with the traffic flowing across those networks having little to no incremental cost of operation.

Therefore, some net neutrality proponents make the case that charging for best-effort bandwidth under ordinary peering and transit agreements and infrastructure simply takes advantage of the consumer. However, charging for premium service (i.e. enhanced or prioritized such as being able to watch the Superbowl live in HD with very low latency) service might make sense since it involves deployment of new infrastructure and higher ongoing operational costs to guarantee those services.

Another area where we need to define net neutrality is with access tiering deserves a more detailed description of what it means and an explanation of how it has been conflated with some of the other network neutrality concerns. Some economists, most notably Hal Varian and Jeffrey Mackie-Mason, have done a substantial amount of work on the potential extraction of "monopoly rents" (i.e., higher prices) by carriers providing networks with access to subscribers. Thus the term "access network" describes networks with broadband or "last-mile" connections to consumers. “Tiering” refers to charging for different grades of service in order to reach those subscribers.

Speaking in broad terms, there are three pervasive viewpoints on the issue of access tiering.

Access tiering appears to be the core issue of debate amongst the two opposing net neutrality camps. There are those that wish to push for a ban on access tiering prior to demonstration of monopoly rent extraction and those who either do not believe it is an issue or feel it should be dealt with on a jurisdiction by jurisdiction basis.

The issue, furthermore, has become tightly intertwined with the verbiage surrounding non-discrimination, transparency, network management practices, and tiering. The Internet is vastly different from telephony and today it is lightly regulated under Title I of the Communications Act.

Hence, one of the key regulatory challenges is how to modernize the language used to define these concepts and shift focus to the technical realities that exist in today’s Internet using the Commission’s existing regulatory framework. The process to address some of these initial issues has already started within key groups and organizations including the FCC.

When they define net neutrality, some net neutrality advocates seek to ban or disallow tiering or network management. Advocates such as Timothy Wu and Susan Crawford have, in the past, taken a rather hard line.

Their philosophical position is akin to the argument that cities, counties, and states should be required to ever increase the width of their highways so as to ensure that traffic, even during rush hour, can move at some minimum acceptable speed.

Under this philosophy, "diamond lanes", "truck lanes", and toll-booths are inherently unfavorable to the common good. The Internet, as a whole, should be a managed public good whereby those traffic engineering standards are in place so that any new application or service can be on a level playing field with all of the others.

The goal in the net neutrality debate then seems to ignore the rather simple fact that the Internet is a network of networks which are all independently operated by cooperating and competing business interests. Thinking of it like a socialized interstate highway system is simply not apropos.

In addition, certain applications do place different requirements on the network. Some applications require extremely low latency and packet loss, like gaming, digital gold currency payments or the Superbowl, while others can more robustly accommodate widely varying congestion conditions, such as email or text browsing.

In my opinion, a third party, comprised of various members of the entire Internet ecosystem, is needed to marry the new and proposed rules of the road with the technical realities of the Internet and its surrounding consumer marketplace.

By allowing the competing and cooperative business, academic, and governmental interests who all operate their own portions of the Internet to have the freedom to innovate and improve Quality of Service (QoS) standards while experimenting with different business models, the Internet will continue to flourish with a whole new set of opportunities through entrepreneur spawned innovation.

The most controversial issue for both sides of the net neutrality debate is access tiering. This calls for a neutral party to begin the challenging process of creating a governance body that can effectively deal with the remaining issues of application compatibility, pricing, transparency and nondiscrimination.

This body must remain neutral on the policy issues related to the access tiering economic model, no matter which framework or frameworks emerge globally. Today, Inter-Stream has the unique opportunity of establishing a process for self-regulation and the development of a global brand enabling all market participants to support their business interests while also supporting new entrants to innovate in ways yet imagined.

Anthem Blanchard

InterStream

DISCLOSURES: Long physical gold, silver, platinum, GOOG, MSFT with no interest in AMZN, AKAM, LLNW, T, AAPL, NFLX, or the problematic SLV, Streettracks Gold ETF Trust Shares or the platinum ETFs.